Welcome to Earth Day, 2000s edition. The decade of 9/11, foreign wars, tech takeovers and financial ruin.

As we entered the 21st century, the world increasingly understood climate change. From natural disasters to failed diplomatic initiatives, we describe some of the most defining environmental developments of the 2000s below. It was yet another disappointing decade, book-ended by economic turmoil, but chock-full of discouraging occurrences that called into question our global commitment to addressing environmental degradation.

Next, check out our final review, a survey of environmental developments during the 2010s.

Table of Contents

2000: Paul Crutzen Anthropocene

In 2000, scientists convened for a conference in Cuernavaca, Mexico. Eventually, frustrated by repeated mentions of the term Holocene to refer to modern times, geologist Paul Crutzen exclaimed that humans have made a geological and ecological imprint sufficient to mark a separate epoch, which he deemed the Anthropocene.

Crutzen was not the first to use the term – limnologist Eugene F. Stoermer had already begun to use the term Anthropocene informally in the 1980s. But Crutzen popularized the term, which now synthesizes scientific recognition of humanity’s irreversible impact on Earth. Interpretations vary as to the formal beginning of Anthropocene, ranging from the first time humans used fire to the first time humans burned fossil fuels at scale.

Is it an event where a scientist popularized an obscure term? Maybe not. But we like to shed light on under-reported stories that nonetheless represent key developments, tangible or not, in the long and winding story of sustainability.

Regardless of our future trajectory as a species, humans have already left a likely indelible impact on our planet. Photos from around the world paint a picture of global destruction that may never be fully rectified.

Over the coming years and decades, will we try to undo the mistakes of our past in the 21st century? We can only speculate.

2002: World Summit on Sustainable Development

10 years after the first Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, 65,000 delegates from over 185 countries convened in South Africa for the World Summit on Sustainable Development. Issues discussed included measures to cut poverty, improve sanitation, improve ecosystems, reduce pollution, and improve energy supply for poor people.

The United States notably boycotted the proceedings in Johannesburg; its only involvement was a brief appearance by Colin Powell with his airplane taxiing on the runway at the airport. This absence symbolized the federal government’s inaction on climate policy during the Bush administration, which climaxed with America’s exit from the Kyoto Protocol in 2005.

Delegates built on Stockholm and Rio to adopt a Johannesburg Declaration, which had less of an environmental focus as it noted threats to the human dimensions of sustainable development. Read the Johannesburg Declaration here.

2003: European heat wave

In the summer of 2003, an anticyclone sitting over western Europe led to an extended and severe heat wave. It was an absolute scorcher, especially in France. 2003 was the warmest summer in Europe since at least 1540. Over 70,000 Europeans died. Crops withered, glaciers receded, and forest fires ravaged the continent.

2003 raised concerns over global warming and Europe’s readiness for climate change. A 2016 study conclusively demonstrated a link between the heat wave and climate change.

Last June, temperatures in France exceeded the record set during the 2003 heat wave. While it’s irresponsible to associate temporary weather events with long-term climate change, extreme weather events serve as a cruel reminder that we live in a warmer world.

2005: The Year of Hurricanes

As a 10-year-old school student living in South Florida, I loved hurricanes. For one, I’d watch Max Mayfield’s advisories from the National Hurricane Center, eager to understand the latest developments in the warm ocean waters. Hurricanes also meant no school, often for days.

2005 marked a record-breaking Atlantic hurricane season, with 31 tropical or subtropical cyclones, 15 hurricanes, and seven major hurricanes. Four hurricanes reached Category 5 status: Emily, Katrina, Rita, and Wilma. Those names sound like they were pulled straight from Lou Bega’s Mambo No. 5; one of them was!

Two of those – Katrina and Wilma – affected South Florida. Katrina made landfall over Miami Beach, a short drive from where I grew up. It was a weak Category 1 hurricane and as such did not seriously impact South Florida. We were spared, but the Gulf Coast was not. Katrina’s impacts are beyond the scope of this article; learn more here.

Wilma was actually stronger than Katrina, reaching 185 mph winds and setting the record for lowest barometric pressure of any Atlantic hurricane ever. Wilma had weakened by the time it made landfall over Florida’s Gulf Coast, but more than 100 miles away in South Florida, we felt Wilma’s wrath.

The 2005 hurricane season had devastating economic and social impacts in multiple countries. But it also served as a wake-up call and a harbinger of what might happen every summer in a warmer world.

2006: Three Gorges Dam

Originally proposed by Sun Yat-sen in 1919, China completed construction on the Three Gorges Dam in 2006. The dam is huge – the largest in the world by far – and provides abundant hydroelectric power. It has a total capacity of 22,500 megawatts, making it the largest power station in the world.

In 2018, Three Gorges generated over 100 billion kilowatt hours of electricity, enough for about one-tenth of China’s power needs. The coal usage avoided by its operation is monumental.

But such a massive engineering project inevitably comes with downsides. Millions of Chinese were forcibly relocated before the dam began operating. The ecological effects alone may make the project decisively net negative. Long story short, Three Gorges is a prime example of a high-risk, high-reward environmental effort.

Similarly to nuclear power, hydroelectric power like Three Gorges constitutes a common environmental dilemma. Dams control floods, produce ample clean power, improve navigation for shipping, and provide jobs. But they also force mass relocations, cause water pollution, and harm ecosystems. Ethical considerations cannot be ignored as humanity makes profound planetary decisions over the coming decades.

2006: An Inconvenient Truth

Al Gore became identified with environmentalism during his time as Vice President under the Clinton administration. He lost the 2000 presidential election by a hair, a major ‘what if’ moment that we will explore in a future article.

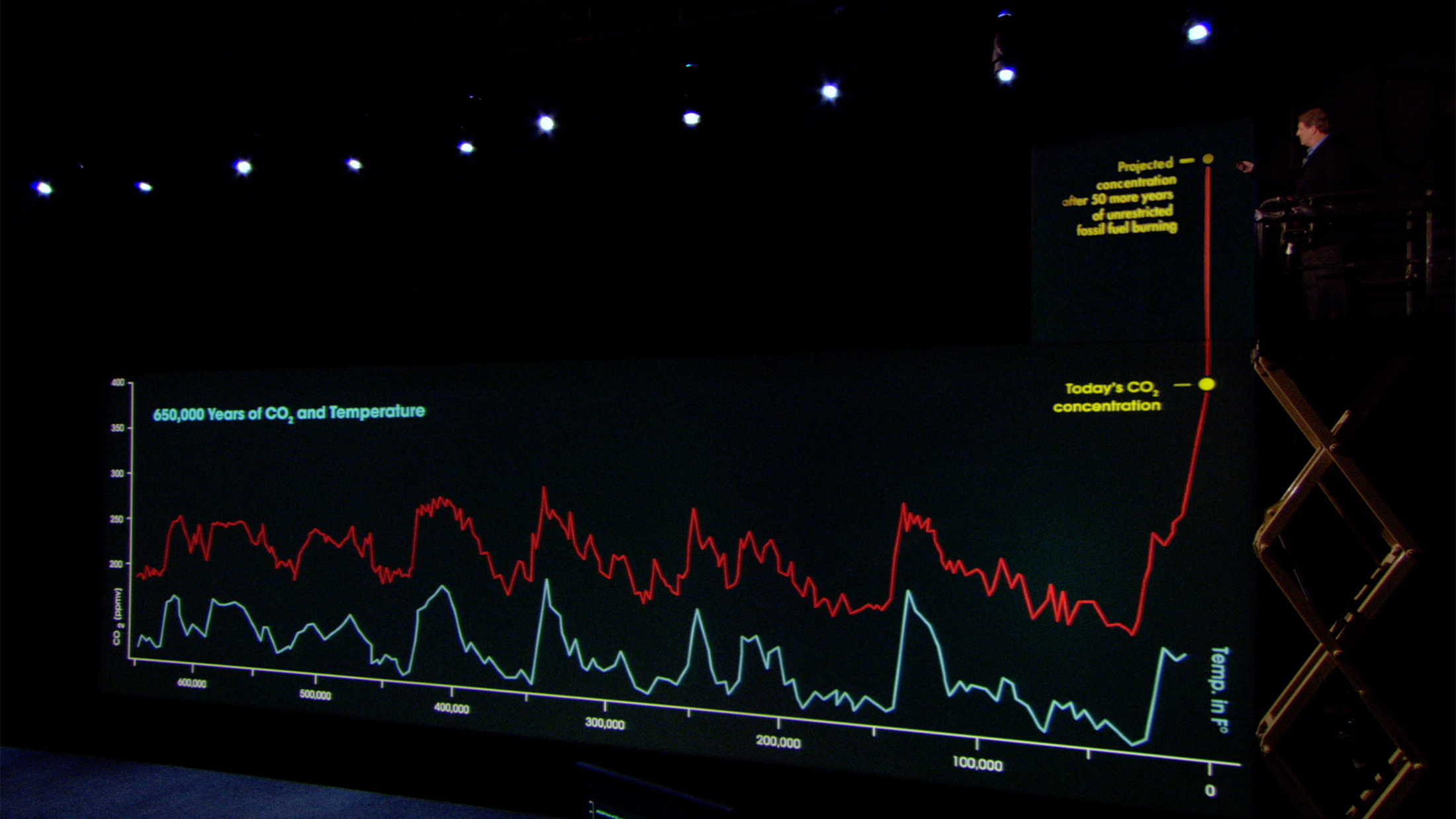

After a few years largely out of public life, Gore made his mark in 2006 by releasing An Inconvenient Truth, a documentary that raised broad awareness of the grave threat posed by climate change. The issue seeped into popular culture; Al Gore and fellow environmentalist Robert F. Kennedy Jr. posed with Julia Roberts and George Clooney on the cover of Vogue.

Gore won a Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. According to Texan climatologist Steven Quiring, An Inconvenient Truth “has had a much greater impact on public opinion and public awareness of global climate change than any scientific paper or report.”

The documentary raised awareness to unprecedented degrees, but it didn’t necessarily translate into action. Even a critically acclaimed documentary made by a former Vice President had a hard time spurring meaningful action on climate change.

If anything, An Inconvenient Truth underscored the challenge of communicating about climate change in a way that sparks both awareness and action. Tomorrow, you’ll read about a young girl from Sweden who has met that challenge head-on.

2006: China overtakes US as biggest CO2 emitter

Decades of rapid economic development led to steadily rising CO2 emissions from a growing superpower. In 2006, following four consecutive years of double digit GDP growth, China’s emissions surpassed America’s by 8%. It symbolized China’s rise and the country’s increased contributions to climate change.

14 years later, China has now contributed most to global warming since 1990, the benchmark year for UN-led climate action.

Spurred mostly by paralyzing air pollution that kills an estimated 1.6 million Chinese annually and palpably reduces quality of life for many others, Chinese officials have invested substantially in wind and solar power and pledged to have carbon dioxide emissions peak by 2030 at the latest as part of the Paris Agreement.

But recently, China’s priorities (and dollars) have shifted. The country still relies heavily on coal and has reduced renewable energy investments (which fell by 39% in the first half of 2019 compared to the first half of 2018). Given China’s heft, climate-related decisions there have amplified effects around the world.

Regardless of these shifting priorities, developments in China have been largely encouraging, with the country on track to meet its climate goals nine years early. “As China moves towards a higher tech and service economy, it is likely to show how the passage to a low-carbon economy and robust and sustainable growth in an emerging market economy can be mutually supportive,” says Nicholas Stern, of the London School of Economics.

2007: Massachusetts v EPA

You may not have heard of this Supreme Court case. Just to clear the air, Massachusetts was one of 12 states (as well as several cities and organizations) involved in this lawsuit aimed at forcing the EPA to regulate carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases as pollutants.

Even the fact that the Supreme Court heard the case was a huge victory for environmentalists, who had previously had a tough time bringing their cause to the highest court in the land. The verdict would delight them even more.

With a 5-4 favorable ruling, the plaintiffs won. Massachusetts v EPA “laid the groundwork for many of former President Obama’s climate policies, including the Clean Power Plan.”

Yes, it took a Supreme Court ruling to require our federal government to recognize the massive pollution caused by greenhouse gases. No, we still haven’t done enough about it.

2008: Coal ash disaster

Burning coal produces a toxic byproduct known as coal ash, which causes numerous health risks given the carcinogens contained in the various metals found in coal ash.

On December 22, 2008, a dike ruptured at a coal ash containment pond in Tennessee, releasing 1.1 billion gallons of coal ash slurry (enough to fill 1,660 Olympic sized swimming pools) across 3,000 acres of nearby land.

The Tennessee coal ash spill released about 40 times as much fossil fuel by volume as the Exxon Valdez oil spill. The accident occurred in a fairly rural area, leading to relatively reduced loss of life.

A Duke study investigated the potential environmental and human health impacts in the immediate aftermath of the spill. Suffice it to say, you don’t want to be anywhere near coal ash, especially if you have preexisting health conditions.

EPA published a Coal Combustions Residuals (CCR) rule in 2015 to regulate disposal of coal ash. Late last year, the EPA initiated efforts to undermine the 2015 rule. The saga of coal ash underlines how quickly and forcefully we must do away with burning coal, for the sake of our lungs and our planet.

2009: Copenhagen accords fail

In regard to the climate movement, 2009 had a cocktail of fear and hope: fear given the global economic downturn caused by the financial crisis, hope given the promise of a global climate summit to be held in December 2009 in Copenhagen. Attendees looked forward to building on the Kyoto Protocol to create a robust emissions reduction framework.

Despite initial optimism, the accords were fairly disappointing, handicapped by an email hack known as Climategate that unleashed a wave of climate denial and stunted political progress. In a prelude to future developments, then-prominent House Republican Mike Pence said the U.S. should not commit to a climate agreement in “the midst of an academic scandal and questionable science revealed in ‘Climategate.’”

One undeniably positive impact of the accords was the creation of a Green Climate Fund, which since 2015 has allocated many billions of dollars to 102 projects and programs, mostly in developing countries.

In retrospect, Copenhagen may have created more goodwill and impact than people often claim. Tomorrow, you’ll read about a landmark agreement made six years after Copenhagen that may prove pivotal as we try to keep warming in check.

That does it for Earth Day, 2000s edition.

No Comments