The Flint Michigan water crisis is alive and well in 2020. The lethal lead contamination of the tap and drinking water from back in 2014 was no secret to national media. Six years later, the predominantly African American town of 100,000 still suffers from the unconscionable public health crisis perpetrated by both city officials and Michigan’s environmental department.

How does lead get in water?

Lead doesn’t naturally occur in water, but chloride does–a negatively-charged, ionic form of chlorine. Chloride, an essential electrolyte, boosts plant photosynthesis and hydrates humans and animals. Chlorine is a purifying compound produced for commercial use and almost never appears naturally.

In high concentrations, chlorine is highly toxic and corrosive. When Flint began piping water contaminated with E. coli and coliform bacteria from the Flint River, the city addressed the problem by increasing chlorine levels, thus corroding the old lead pipes and gradually poisoning its citizens.

Ingesting any amount of lead is harmful. Detrimental bodily effects from significant lead exposure include cardiovascular and kidney disease; behavioral issues; stunted IQ and brain development in fetuses, infants, and children; and high blood pressure and decreased fertility in adults.

Increased lead concentrations in Flint’s water induced a 58% increase in fetal deaths from October 2013 to the end of 2015. Further, the 2014-2015 outbreak of Legionnaire’s disease resulted in at least 12 fatalities and 87 total cases. Chlorine normally keeps the Legionella pneumophila bacterium in check, but its reaction to lead, other metals, and organic matter–reducing chlorine concentration–in Flint’s piping system likely caused the bacteria to multiply, research finds.

A look-back of the Flint Michigan water crisis

2011-2015

November 29, 2011

Michigan governor Rick Snyder authorizes a state takeover of the city of Flint after concluding that its financial distress has no immediate solution, installing emergency financial manager Michael K. Brown to lead recovery efforts.

April 25, 2014

Under Brown’s authority, Flint divests from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department and invests in the Karegnondi Water Authority (KWA) to reduce municipal costs. The temporary switch requires the KWA to pull water from the Flint River before a new pipeline is built. City officials project cost savings of $200 million over 25 years with the new plan.

May 2014

Flint residents report foul-smelling, brownish water coming from their taps, but city officials largely ignore them.

August 2014

Tests show evidence of E.coli and coliform bacteria in Flint drinking water. The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) attempts to fix the problem by amplifying chlorine levels in the water.

October 2014

General Motors shuts off KWA water sources, citing concern about the corrosion of its engines following increased chlorine levels. Apparently, auto parts are worth more than people’s lives in this automobile manufacturing hub.

January 2, 2015

Flint violates the Safe Drinking Water Act. Total trihalomethanes (TTHM), the disinfection byproducts of chlorine and organic matter, reach unsafe levels.

February 25, 2015

City officials test the water in resident and activist Lee Anne Walters’ home and find lead content of 104 parts per billion (ppb). The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) limit for lead in drinking water is 15 ppb, and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) limit is 10 ppb. An independent study by Virginia Tech researchers finds levels as high as 13,200 ppb, dramatically exceeding the hazardous waste standard of 5,000 ppb.

Late April 2015

The MDEQ informs the EPA that the Flint Water Treatment Plant did not carry out corrosion control treatment.

September 6, 2015

Virginia Tech researchers express extreme concern about the lead concentrations in Flint’s water. Dr. Marc Edwards tells Michigan Radio they are “some of the worst that I have seen in more than 25 years working in the field.”

September 25, 2015

Flint issues a public health advisory to residents, advising them to “reduce exposure to lead as much as possible.”

October 16, 2015

Flint reverts back to their original Detroit water supplier.

December 14, 2015

The damage has already been done. Newly-elected mayor Karen Weaver declares a state of emergency, seeking immediate remedial action from her city council.

2016-2020

January 2016

Governor Snyder, President Obama, and the EPA declare states of emergency as well, opening the door for Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) funds to help resolve the crisis and for the EPA to take action.

January 12, 2016

Governor Snyder sends in the National Guard to distribute faucet filters and bottled water to residents.

March 2016

Governor Snyder demands a prompt investigation into the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services and its handling of the 2014-2015 outbreak of Legionnaire’s disease in Genesee County.

April-July 2016

Michigan attorney general Bill Schuette files charges against several state officials and two corporations, citing “felony charges including misconduct, neglect of duty and conspiracy to tamper with evidence.”

December 10, 2016

The US Senate approves a $100 million bill to fund decontamination efforts in Flint’s water supply grid.

January 24, 2017

MDEQ reports that municipal water tested below the federal lead action level from July to December 2016, but residents should “continue using filtered water for drinking and cooking.”

February 17, 2017

The Michigan Civil Rights Commission contends “deeply embedded institutional, systemic, and historical racism” backed city officials’ decision to willingly supply the majority-black city of Flint with contaminated river water.

March 17, 2017

The EPA expedites the allocated $100 million of federal funding towards water infrastructure improvements and removal and restoration of lead service lines in Flint.

November 29, 2017

Flint seals the deal on a 30-year lease deal with the Great Lakes Water Authority that guarantees the city’s access to clean water from Lake Huron and a greater portion of the $100 million designated by the EPA for a water infrastructure overhaul.

December 31, 2017

Flint has located and reinstituted over 6,000 lead service lines.

April 4, 2018

Michigan ends Flint’s state receivership after six years, freeing the city from state controls and the veto powers of the Receivership Transition Advisory Board.

April 6, 2018

Governor Snyder announces the state will stop giving free bottled water to residents following MDEQ’s assessment. The report says municipal water has tested below the federal lead action level from July 2016 to March 2018, but thousands of Flint residents will continue to drink water from lead-contaminated pipes.

February 12, 2019

At last, the city of Flint promises to pinpoint the remaining lead pipes connected to residential areas and subsequently remove them.

November 2019

Newly-elected mayor Sheldon Neeley considers switching back to KWA, regretting the city’s lack of control over its own water.

April 13, 2020

Flint City Council splits 4-4 on a vote to commission L. D’Agostini and Sons to construct a pipeline linking Flint to its backup water supply at the Genesee County Drain Commission. This project would put Flint in compliance with the Safe Water Drinking Act.

Flint Michigan water crisis today

Despite municipal and federal efforts to remove the lead pipelines delivering water to residential areas, Flint residents and visitors are still wary. They often only drink bottled water, distrusting the city officials who lied to them for so many years and told them their water was “safe.”

Although lead levels in Flint’s water are now below federal lead action levels, no amount of lead in water is healthy for domestic use. Residents suffered skin rashes and hair loss, and long-term effects will become more evident as Flint’s current children become adults.

As of March 12, 2020, $87 million of the $100 million allocated for water infrastructure improvements has not been used because Flint filed very few reimbursement requests. Time is running out–the grant expires on December 31, 2021.

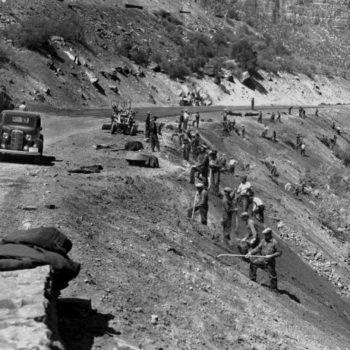

Moving forward, local officials have a responsibility to ensure that every single lead pipe is pulled from the ground, including pipes that don’t currently connect to residents’ homes. The Flint Michigan water crisis will never end until the government takes the necessary steps to enact and enforce robust policy. Maybe they should hire unemployed Americans. I don’t know. But they need to do something. One thing they can do is file reimbursement requests to fund research to further decrease the lead parts per billion in drinking water to at least convey trust to rightfully dubious residents.

No Comments