Welcome to the second installment in our Earth Day series, the 1980s. The decade started with a win for environmental justice and the literal “defining moment” for sustainable development.

Everything was bigger in the 1980s – big hair, leg warmers, and boom boxes, big phones, big junk bonds and trading scandals, and, of course, the advent of MTV and personal computing. It also may have been the decade in which we “lost Earth”.

The second half of the decade included one of the most successful international environmental negotiations and brought climate change and its impacts to the public consciousness for the first time. This is Earth Day, 1980s edition.

Table of Contents

1980: Superfund

Earth Week’s first article mentioned the 1978 declaration of a federal emergency in the Love Island community in upstate New York, where a chemical company dumped 21,000 tons of toxic chemicals into a local canal. This is the first major environmental event that defined Earth Day in the 1980s.

By 1980, the lobbying of the local residents, who were affected by illness, birth defects, and miscarriages from the chemicals, finally paid off.

Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, commonly known as Superfund. This law requires polluting industries to fund the cleanup of toxic sites.

With Superfund, communities could wield some legislatively mandated power to hold industry accountable to remediating land after years of exploitation. Since 1980, Superfund has successfully funded the cleanup of more than 750 sites across the nations, although the program has struggled with mismanagement and inefficiency and is often the unwitting target of budget cuts.

1980: Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act

Passed at the tail end of the Carter administration, the Alaska National Interest Land Conservation Act (ANILCA) was one of the largest and most comprehensive pieces of conservation legislation ever passed by Congress. It increased the acreage of park lands managed by the National Park Service (NPS) in Alaska to over 54 million acres, which represents 65% of the total land in the National Park System.

ANILCA is the first and only example of public lands legislation that contains “subsistence use” provisions. Subsistence regulations enable Alaskan Native peoples and rural communities to continue to practice traditional customs of living off the Alaskan wilderness for food, shelter, fuel, clothing, tools, and transportation.

Every so often, the United States designates new national parks, but none have been nearly as large as those found in our nation’s Last Frontier. Today, the top four largest national parks are found in Alaska, the largest being Wrangell–St. Elias at over 8 million acres. That’s larger than Rhode Island, Delaware, Connecticut, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Hawaii, and Maryland combined!

1982: IWC

People have been hunting whales since at least 3000 BC. Industrial whaling emerged in the 17th century, powered by the advent of whaleships. Before the Industrial Revolution, whale blubber was commonly used to create oil.

Demand for whale meat and blubber caused over-harvesting of whales; at times, over 60,000 were killed annually. Recognizing the imminent depletion of whale populations, governments collaborated to sign the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) in 1946.

But real international action to protect whales did not proceed until decades later. “Save the Whales” is a cliche for environmentalists at this point. But, in 1982, the world actually mobilized to make it happen. The International Whaling Commission adopted a global moratorium on commercial whaling, in response to decades of protest from scientists and activists (see: the great work of Greenpeace).

The moratorium is supposedly binding, but Norway, Iceland, Japan, and Russia exploit loopholes in the agreement to continue hunting whales. Thousands of whales are still killed intentionally every year, and many die from anthropogenic causes like shipping collisions.

1983: Brundtland Commission

Ten years after the 1972 UN Conference on the Human Environment, environmental challenges and inequality continued to grow as industrialization progressed. In response, the UN established the Brundtland Commission to rally countries to reconcile their economic growth with environmental protection.

The Commission was led by Gro Harlem Brundtland, the former Prime Minister of Norway. Its legacy lies in the 1988 “Our Common Future” report, which defines sustainability, the core of our mission here at the Sustainable Review, as it is most commonly interpreted today: “meeting our current societal needs without impeding the ability of future generations to meet their needs.”

The Brundtland Commission recommended that in order to protect humans and the planet, we must act on the two most pressing challenges of the 21st century: climate change and poverty. The commission urged the world to see these issues as intersectional and interrelated rather than separate and siloed. In order to solve one, both must be solved.

…the “environment” is where we live; and “development” is what we all do in attempting to improve our lot within that abode. The two are inseparable.”

The Brundtland Commission is also credited with putting forth the conceptual framework for the three pillars of sustainable development: economic growth, environmental protection, and social equality, which would later be coined the “triple bottom line.” This is the core recognition that informed the creation of Agenda 21 (first action plan for sustainable development) in 1992 and, more recently, the 2030 Agenda and the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

1986: Chernobyl

Chernobyl isn’t just the name of a hit HBO docuseries. The nuclear disaster was so influential that it transcends Earth Day history in the 1980s too.

On April 26, 1986, what started as a routine safety test on the No.4 nuclear reactor at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in northern Ukraine ended in the worst nuclear disaster in history. The reactor explosion killed two of the operations staff, and 134 station staff and firemen died, many of which died from radiation exposure.

It is estimated that 9,000 to 16,000 fatalities throughout Europe can be attributed to the release of radioactive materials and associated air pollution. The cleanup of this disaster likely won’t end until 2075.

The accident at Chernobyl understandably promoted great skepticism and concerns about fission nuclear reactors around the world. Though new and rigorous safety standards for reactors were developed, the resulting anxiety and hostility toward nuclear energy persists today. Nuclear power is far cleaner than fossil fuels, but with traumatic incidents like Chernobyl on people’s minds, nuclear has felt too dangerous to many to justify continued investment.

1987: Montreal Protocol

You know how big hair was popular in the 80s? You can thank hairspray. That recognizable hiss as the cloud of hairspray escapes the can came from Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which acted as a propellant in aerosol spray cans and as coolants for devices like air conditioners and refrigerators. At the time, people viewed CFCs as a technological marvel – a safer, healthier alternative to refrigerants of the past that used toxic and flammable chemicals.

However, the widespread use of CFCs had an unexpected consequence for the environment and human health. In the 1970s, scientists discovered that CFCs break down high in the atmosphere and poke holes in the ozone layer. Acting as the Earth’s sunscreen, ozone keeps deadly UV radiation from the sun from reaching the planet’s surface. With this recognition, nations mobilized quickly to ban the use of CFCs from spray cans, but they allowed their continued use in air conditioners, electronics manufacturing, refrigeration, and more.

A decade later, the discovery of the Antarctic ozone hole, which exceeded the size of the United States, prompted the world to meet and negotiate the Montreal Protocol, which created the framework for an outright ban of CFCs globally.

Montreal is widely recognized as the most effective international environment-related agreement to date. It was the first treaty universally ratified by 193 countries and enabled the hole in the ozone layer to begin to heal. What can the Montreal Protocol teach us about creating successful climate agreements?

1988: CO2 in atmosphere surpasses 350 ppm

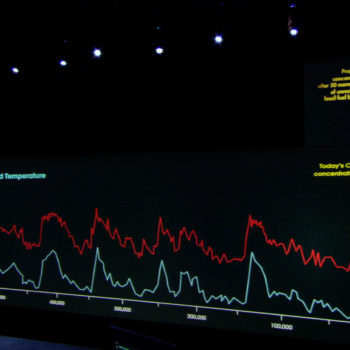

Before the Industrial Revolution, global atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations stood at roughly 275 parts per million. Meaning, for every million particles of air, 275 were carbon dioxide.

With the Industrial Revolution, humans began to burn fossil fuels (particularly coal) to power and strengthen the economy. The first major downside to fossil fuels was apparent to the naked eye, it caused air pollution which showed itself in the form of smog. But over time, scientists realized the other big flaw: burning fossil fuels emits additional carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and that carbon dioxide traps heat in the atmosphere that would otherwise escape into space.

For a long time, humans were not burning enough fossil fuels to drastically alter atmospheric CO2 concentrations. In the 20th century, particularly after World War II, that changed. Planes, trains, and automobiles couldn’t power themselves after all. In 1988, CO2 concentrations surpassed 350 ppm.

Why is that a big deal, you may wonder? Climate scientists have demonstrated that 350 ppm is considered the threshold beyond which we cannot secure a healthy and livable planet. Any level of atmospheric CO2 above 350 ppm poses serious and detrimental threats to the biosphere. That magic number is literally the namesake for 350.org, one of the most influential environmental organizations.

Before 1988, it had been a jaw-dropping 3 million years since the atmosphere contained this level of carbon dioxide! You wouldn’t recognize the Earth of 3 million years ago. That was back even before our human ancestors wielded stone tools. The climate was a few degrees hotter and the sea level was between 15-25 meters higher.

Last year, the atmosphere reached a startling 415 ppm. Continued growth at this pace would bring us well above the limited 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming aimed for in the Paris Agreement. Staying below 1.5 degrees warming is essential to temper some of the worst effects of climate change, sea level rise drowning small island nations, extreme heat causing protracted drought, and species loss, among others.

1988: Dr. James Hansen’s Congressional Testimony

The same year that carbon dioxide concentrations exceeded 350 parts per million, a NASA scientist named Dr. James Hansen testified before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee about the urgency of climate change. Dr. Hansen alerted Congress that writing off the causes of years of unprecedented high temperatures as natural variations of the climate was not only inaccurate and unscientific, it was irresponsible. He emphasized that rising temperatures stemmed from the greenhouse effect – burning fossil fuels caused a buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere -and the problem should be addressed as soon as possible.

“It is time to stop waffling so much and say that the evidence is pretty strong that the greenhouse effect is here.”

This was quite a progressive stance for the time; although the science was clear, no one had ever come out and said to Congress before that human activity had already had an irreversible effect on the climate for decades to come. Dr. Hansen catalyzed the United States to begin conversations on what to do about climate change.

This was, of course, before the persistent and organized fossil fuel lobby masked the truth of climate change and sowed skepticism about the science behind it. Since the 2015 Paris Agreement alone, the five largest oil companies have spent a combined $1 billion on misleading climate-related branding and lobbying.

We think James Hansen’s testimony to Congress best defined the meaning behind Earth Day in the 1980s.

1988: IPCC established

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was established in 1988 to assess the risk of climate change based on the latest science. Every five to seven years, the IPCC convenes thousands of global experts to release reports that summarize the most critical developments in climate science and solutions to inform international policy-making and negotiations.

Since 1988, the IPCC has released five comprehensive assessments, with the sixth due for release in 2022. They periodically release special reports that go-in-depth on a single issue in climate change, such as the impacts of 1.5°C warming, the most recent being the special report on the oceans and cryosphere.

Over time, the exhaustive IPCC reports have made it progressively clearer that we face a ticking time bomb. And the longer we wait to act, the worse it will get (and thus the harder it will be to fix).

1989: Exxon Valdez oil spill

This is the final environmental event that defined the Earth Day movement in the 1980s.

Exxon Valdez oil spill occurred when an oil tanker owned by the Exxon Shipping Company collided with a reef and spilled 11 million gallons of crude oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound. At the time, it was the worst oil spill that had ever occurred! Spoiler alert for the 2010s.

The resulting oil slick impacted 1,300 miles of coastline in just a couple months. That’s roughly equivalent to half of the California coast, according to NOAA data.

Exxon Valdez decimated the formerly pristine and natural Prince William Sound. The oil exposure killed 250,000 sea birds, 3,000 otters, 300 seals, 250 bald eagles and 22 killer whales. Fishermen went bankrupt, and the economies of small shoreline towns suffered. The cleanup cost Exxon about $2 billion and habitat restoration cost $1.8 billion.

One of the most effective methods for oil removal was spraying hot water from high-pressure hoses. This method caused even more ecological damage, killing plants and animals in its wake. 31 years later, some of the crude oil still remains on the surrounding beaches.

That does it for Earth Day, 1980s edition. Did the consequences of the Exxon Valdez disaster convince Congress to hold oil companies accountable?

Check out Earth Day 1990’s to find out.

No Comments