Welcome to Earth Day, 1990s edition.

The U.S. population was 250 million. The Berlin Wall was collapsing. Fresh Prince, Home Improvement and Friends filled our TV screens. Gameboys were the ‘next big thing’. Yes, frosted tips, flat tops and boy bands everywhere.

These are the biggest events of the environmental movement of the 1990’s that dominated the decade.

Table of Contents

1990: First IPCC climate report

For Earth Day 1980s, we wrote about the formation of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 1988. In Earth Day 1990s, we are highlighting its first climate report.

The body’s initial task was to review and recommend policies based on the panel’s findings. Two years after the IPCC formed, the group published its first report on climate change.

The report included scientific data and socioeconomic analysis, and highlighted potential response strategies and ideas for future international conventions related to climate.

The scientists saw the writing on the wall, and they spoke up. As usual, nobody listened.

Since 1988, the IPCC has delivered five Assessment Reports through five cycles, and is widely considered to be the most comprehensive scientific report on climate change in the world. The Panel has been critical in determining the necessary guidelines for policymakers to make sweeping changes that cross borders. Without it, a coordinated global response would be less likely.

1991: Sweden enacts carbon tax

Sweden is obviously not perfectly representative of every other country. Its carbon tax hasn’t even been particularly effective.

But the country’s ability to decouple economic growth and emissions demonstrates that it can be done.

Experts from many disciplines have long promoted a carbon tax as the best economic solution to climate change. Put simply, greenhouse gas emissions are a negative externality that often go unrecognized economically.

Imagine if you repeatedly spilled milk as a kid and your parents basically told you the floor would magically absorb the milk, so you wouldn’t be reprimanded. That’s how we’ve viewed greenhouse gas emissions for centuries.

Our planet is full of excess greenhouse gas that we haven’t cleaned up, largely because we don’t either incentivize anyone to clean up the mess or punish anyone for making the mess. A carbon tax elegantly does both.

1991: Mt. Pinatubo

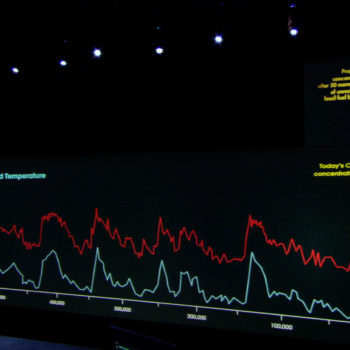

If you look closely at the graph of carbon dioxide concentrations we posted in yesterday’s article, you’ll notice a slower rise in the early 1990s. That wasn’t an accident. You can thank the largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century: Mount Pinatubo.

Pinatubo erupted violently in 1991. It was the Goliath of volcanic eruptions, releasing 10 billion tons of magma and 20 million tons of sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere.

How can volcanoes so greatly influence global weather patterns? They release particles into the atmosphere – particularly sulfur dioxide – that in sufficient quantity and intensity can effectively block out some solar radiation.

Many geoengineering proposals effectively try to replicate the impacts of cataclysmic volcanic eruptions like Pinatubo. But these ideas are inherently risky and reflect a misinformed understanding of nature that has gotten us to this perilous point as a planet.

As usual, if we leave nature to its own devices, we’ll be better served than applying irrational anthropogenic ideas. That would only exacerbate a disaster of our own doing. Major natural disasters are defining moments for exploring the history of Earth Day and the subsequent environmental movement in the 1990s.

1991: Kuwaiti oil fires

The Kuwaiti oil fires were caused by Iraqi military forces setting fire to a reported 605 to 732 oil wells along with an unspecified number of oil filled low-lying areas, such as oil lakes and fire trenches, as part of a scorched earth policy while retreating from Kuwait in 1991 due to the advances of Coalition military forces in the Persian Gulf War. The fires were started in January and February 1991, and the first well fires were extinguished in early April 1991, with the last well capped on November 6, 1991.

This was a catastrophic event with a severe environmental impact. According to the 1992 study from Peter Hobbs and Lawrence Radke, daily emissions of sulfur dioxide (which can generate acid rain) from the Kuwaiti oil fires were 57% of that from electric utilities in the United States, the emissions of carbon dioxide were 2% of global emissions and emissions of soot reached 3400 metric tons per day.[40][41]

In a paper in the DTIC archive, published in 2000, it states that “Calculations based on smoke from Kuwaiti oil fires in May and June 1991 indicate that combustion efficiency was about 96% in producing carbon dioxide. While, with respect to the incomplete combustion fraction, Smoke particulate matter accounted for 2% of the fuel burned, of which 0.4% was soot.”[With the remaining 2%, being oil that did not undergo any initial combustion].

Yet, the bigger story here is one of human behavior and priorities. Military conflict over scarce resources causes humans to behave in strange ways, and act destructive accordingly. If we are not careful and calculated about the way we treat these precious earth resources, the situation will only become more dire and people will act more desperate. One can only imagine a world without regularly available resources like oil, or even potable water.

1992: Earth Summit

The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), also known as the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit, the Rio Summit, the Rio Conference, and the Earth Summit (Portuguese: ECO92), was a major United Nations conference held in Rio de Janeiro from 3 to 14 June in 1992.

Earth Summit was created as a response for Member States to cooperate together internationally on development issues after the Cold War. Due to issues relating to sustainability being too big for individual member states to handle, Earth Summit was held as a platform for other Member States to collaborate. Since the creation, many others in the field of sustainability show a similar development to the issues discussed in these conferences, including non-governmental organizations (NGOs).[1]

1994: Costa Rica

In 1994, Costa Rica amended its constitution to formally establish a right to a healthy and ecologically balanced environment. This was a novel move, and although predominantly symbolic, it fueled the country’s environmental movement into a new generation of lawmakers and activists that prioritized the sense of urgency needed to combat climate change and ecological degradation.

Costa Rica stands today as one of the world’s leaders in government-led environmental initiatives. The pacifist nation runs on practically 100% renewable energy, becoming the first of its kind. By making environmental protection an essential component of a citizens’ rights, Costa Rica provided a model for countries around the world to emulate. We can learn a lot from this tropical paradise as we think about applying successful environmental strategies globally.

1997: Kyoto Protocol

In December 1997, governments convened in Japan to adopt an international treaty on climate change. The result was the Kyoto Protocol, the first international treaty aimed at controlling and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Kyoto placed the blame squarely on industrial economies for contributing to climate change. It mandated that 37 industrialized nations plus the European Community cut their emissions by 5% from 1990 to between 2008 and 2012. The treaty exempted over 100 developing nations, including China and India.

Upon entering office in 2001, President Bush removed the United States from the Kyoto Protocol (it wouldn’t be the first time a US President removed America from a major climate change treaty, as you’ll read about on Thursday). America’s absence fatally delegitimized the treaty.

1997: Toyota Prius

Toyota began selling the Prius in 1997. The Prius was the first mass market vehicle that had some semblance of electric power. Despite its utilitarian design and relatively lackluster performance, it achieved both widespread popularity and pop culture recognition and acceptance. Toyota has sold tens of millions of Priuses, with seemingly no end in sight.

For decades, the Prius has reigned supreme as a mass market electric vehicle. But today, we’re on the precipice of an electric car revolution. Tesla’s rise in the 2010s served as a mere appetizer for what will come in the 2020s. Just about every major global automaker plans on prioritizing EV technology over the coming decade.

Current events may hasten the demise of the internal combustion engine, and not a moment too soon. Earlier this week, the price of oil went negative, meaning oil drillers had to pay others to store their gooey product. Why did this happen? Long story short, a lack of demand due to the coronavirus. Eventually, such low prices will bankrupt many oil and gas companies.

Today, the Prius is emblematic of Earth Day-inspired environmentalism in the 1990s.

1998: Super El Nino

What is El Nino? Basically, it’s an inversion of ocean temperatures (and thus wind patterns) in the Equatorial Pacific that creates havoc in the form of flooding, drought, and crop failures among other damage. El Ninos occur every few years and normally aren’t too rough. But once in a while, Super El Ninos develop.

One such event occurred in 1998. That year’s El Nino was monstrous; it caused an estimated 16% of global reef habitat to die, induced extreme rainfall in the Horn of Africa that caused a fever outbreak, caused one of Indonesia’s worst droughts, brought record rainfall to California, and catalyzed 11 super typhoons in the Western Pacific.

You might wonder what’s the matter with natural weather events? Normally, nothing. But recent research has demonstrated worrisome trends regarding the frequency and extremity of future El Ninos, particularly “super events” like the winter of 1998.

That Super El Nino foreshadowed future warming. 1998 was the warmest year on record at the time. Not only will those become more frequent in a warmer world, but they will become more potent. Bottom line: that’s bad news bears.

Super El Ninos will exacerbate some of the worst impacts of climate change such as stronger droughts, fiercer floods, and greater hurricanes. The more we throw our planet into disequilibrium, the stronger Mother Nature will respond in fury.

1999: Global population reaches six billion

For hundreds of thousands of years, the global population of humans didn’t expand materially. It took 200,000 years for the population to reach one billion in 1804.

With the Industrial Revolution, that changed…quickly. We then reached two billion in 1927, three billion in 1960, four billion in 1974, and five billion in 1987.

As the dawn of a new millennia appeared, the global population reached six billion in 1999. The previous two centuries of exponential population growth had proven Thomas Malthus wrong.

Planet Earth is abundant and rich. For basically the entirety of our existence on Earth, we have perverted our planet’s abundance by seeing the world as limitless.

That mindset wasn’t necessarily problematic for most of human evolution. But ultimately, our planet is finite. Every new human is another mouth to feed and quench. This realization led us to the first Earth Day in 1970, by the 1990s our realization came along with a major population spike.

Sure, that sounds immoral and callous. Nonetheless, sometimes hard and uncomfortable truths need to be faced head on.

That’s it for Earth Day, 1990s edition. As we wrap up Earth Week over the coming days, think about how you can shift your mindset about the bigger planet you live on in the context of the last five decades of change.

No Comments